Activity Cost Driver For Production Scheduling

Posted : admin On 04.09.2019- Activity Cost Driver For Production Scheduling

- Production Scheduling Template

- Examples Of Activity Cost Drivers

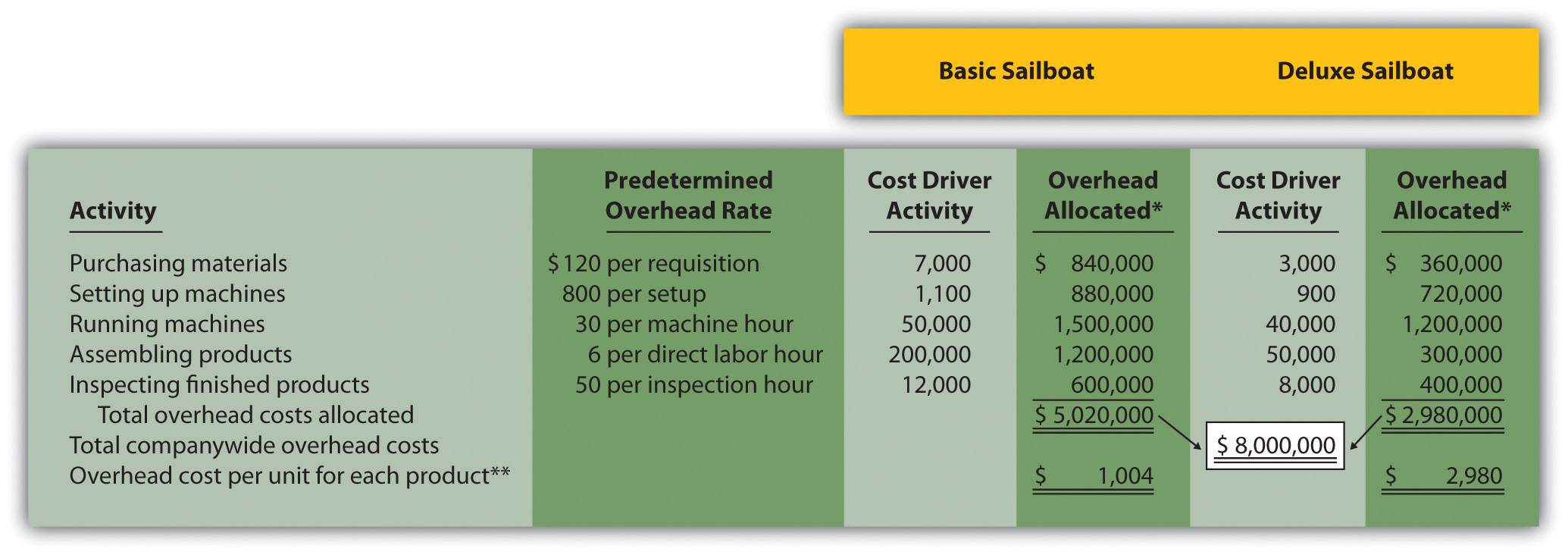

Cost Allocation Example. Dialglow Corporation manufactures travel clocks and watches. Overhead costs are currently allocated using direct labor hours, but the controller has recommended an activity-based costing system using the following data: Activity. Cost Cost Driver. Clocks Watches. Mar 29, 2019 An activity cost driver is a component of a business process. Activity cost drivers are used in activity-based costing, and they give a more accurate determination of the true cost of a business.

Production and manufacturing run on timelines. You receive orders, sometimes concurrently, and you plan the steps in your manufacturing schedule to ensure parts of the process are completed in proper sequence as efficiently as possible. Creating an effective and efficient production schedule can cut payroll costs and keep frustration to a minimum.

TL;DR (Too Long; Didn't Read)

Production scheduling is the process of syncing and planning the steps in the manufacturing process to ensure that production runs smoothly and customers receive what they ordered on schedule.

Activity Cost Driver For Production Scheduling

Areas of Production Scheduling

- Procurement: Production can't proceed if you don't have the materials necessary for manufacturing. Procurement scheduling is an art and a science that involves keeping enough on hand without carrying a bloated inventory. You can tighten procurement systems by using digital or manual spreadsheets to track inventory and by developing relationships with suppliers who can get you what you need consistently and quickly.

- Personnel: Planning and scheduling employee time is critical to developing a successful production work flow plan. There should be enough workers on hand to finish projects within the promised time frame but not enough to bloat your payroll or create inefficiencies by crowding your work space. It helps to understand the strengths and weaknesses of each staff member so you can leverage employee skills and circumvent potential difficulties.

- Machinery: Like your employees, your equipment has a limited number of capacity hours that should be scheduled thoughtfully. Machines should be well maintained according to a schedule that doesn't take them out of production any longer than necessary.

Tools for Scheduling Production

- Software: Once the logistics of your production schedule become complex enough to bog you down, there is a range of software options available to help you manage the details. Programs such as Monday.com and Protected Flow Manufacturing help you to set priorities, coordinate processes and manage staffing.

- Written documents: If your production processes are relatively simple, you may be able to effectively create useful and meaningful lists so team members and managers have a clear idea of what needs to happen and in what order. Timelines and flow charts can help to provide useful visuals to help staff understand how processes interface.

- Custom spreadsheets: You can also design your own spreadsheets to plan and communicate work flow. Custom spreadsheets offer the advantage of being tailored specifically to your company and your processes. They pose the disadvantage of potentially being less robust or nimble than a software system designed by professionals drawing on a deeper and broader database of scheduling tools and knowledge.

Obstacles to Effective Production Scheduling

- Poor communication: No matter how good your production scheduling, it won't be effective unless your crew is kept in the loop and knows what needs to be done. Your team should have systems in place for conveying an overall plan and also relaying updates.

- Outdated systems: If your business is growing at a healthy clip, your systems and software will periodically become obsolete because the processes they manage will be continually evolving. For successful production scheduling, evaluate your processes and information systems periodically and update them as needed.

- Unreliable vendors: If your vendors don't come through with the materials you need in the time frame they promised, you could find yourself with people and machinery scheduled for processes that cannot move forward. When you need inventory urgently, make sure your vendors know that timing is critical. If they consistently don't come through for you when you need them, find other vendors.

The Importance of Strategy

Production scheduling isn't simply a matter of laying out steps and then waiting for the work to happen. Your entire approach to your manufacturing schedule should be organized around systems and processes that specifically make sense for your business. Decide whether it makes more sense for your company to stay well ahead of the game to aggressively avoid shortfalls or whether you prefer the tightness of a lean manufacturing approach. Track the success of different strategies and collaborate with coworkers to build a shared knowledge base.

Assign the batch cost to the product that required the batch activity? Maybe not!

Production Scheduling Template

BY ALAN VERCIO AND BILL SHOEMAKERExamples Of Activity Cost Drivers

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||